The story of astronomer and polymath Benjamin Banneker (1731–1806) is one of dignity and ingenuity against the backdrop of slavery and racism.

Maryland began the 18th century as a plantation colony and slave society. Deprived of liberty and deadened by monotony, exhaustion, and the constant threat of violence, African and African American slaves labored in iron furnaces, caulked ships, and – most lucratively for their white overlords – tobacco plantations throughout the state.

But unlike the vast majority of African American Marylanders at the time, Benjamin Banneker did not suffer a life of bondage.

Frank Schulenburg

The son of a former slave, Banneker was born free on November 9, 1731, in Patapsco Valley, Maryland, and grew up on his family’s remote and vast tobacco farm. To those who knew him, or knew of him, Banneker stood out simply for being a free black youth who could read and write. But he made his first truly astonishing accomplishment in his early 20s, when he hand-carved a wooden striking clock that is alleged to have kept perfect time. Given that most people in the area had not seen a timepiece before — they still typically gauged time based on the position of the Sun in the sky — his clock fascinated Marylanders who flocked from miles around to see it.

Under different circumstances, the self-taught clockmaker might have caught the attention of the scientific community, where Banneker’s clear talents could have been nurtured. But the prejudices of 18th-century Maryland made this impossible.

Just a few years later in 1759, his father Robert died, leaving Benjamin to look after his mother and assume full responsibility for running the farm. For more than a decade, Banneker had to assume the life of a full-time farmer and only part-time gentleman scientist.

This could easily have been the end of Banneker’s story. In fact, he had already sold off some of his land in preparation for a quiet retirement when, in 1771, the Ellicotts — a Quaker family from Pennsylvania — established a gristmill just a few miles down the road from the tobacco farm. Banneker befriended George Ellicott, a land surveyor with a passion for astronomy, who loaned him technical books and a set of astronomical instruments. This small act of kindness was all Banneker needed. While American patriots were revolting against the British Empire, he finally began his journey proper into the realm of science and astronomy.

At the age of 58 – the same year that George Washington was elected the first President of the United States, in 1789 — Banneker accurately forecast his first total solar eclipse. His success galvanized him to start thinking of publishing an almanac — a publication containing astronomical, meteorological, and other useful information for the coming year.

Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society

But the almanac would have to wait, as the next opportunity to put his freshly honed scientific skills to use came in a different form. In 1791, engineer Andrew Ellicott, George’s cousin, was so impressed with Banneker’s mathematical calculations that he invited him to assist in plotting the boundary lines for the new federal district — within which the new national capital, the City of Washington — would be built.

The Georgetown Weekly Ledger used Banneker’s involvement in the project to refute then Secretary of State and future President Thomas Jefferson’s “suspicion,” published in 1781 in his infamous Notes on the State of Virginia, that “the blacks… are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.” The article stated: “Benjamin Banniker [’s] . . . abilities, as a surveyor, and an astronomer, clearly prove that Mr. Jefferson’s concluding that race of men were void of mental endowments, was without foundation.”

Returning to the farm, Banneker could finally resume work on his almanac in earnest. Studying alone, he calculated tide times, the time of sunrise and sunset throughout the year, the phases of the Moon, the changing positions of the planets, the occurrence of eclipses, predictions for seasonal changes, and when pests would be likely to return.

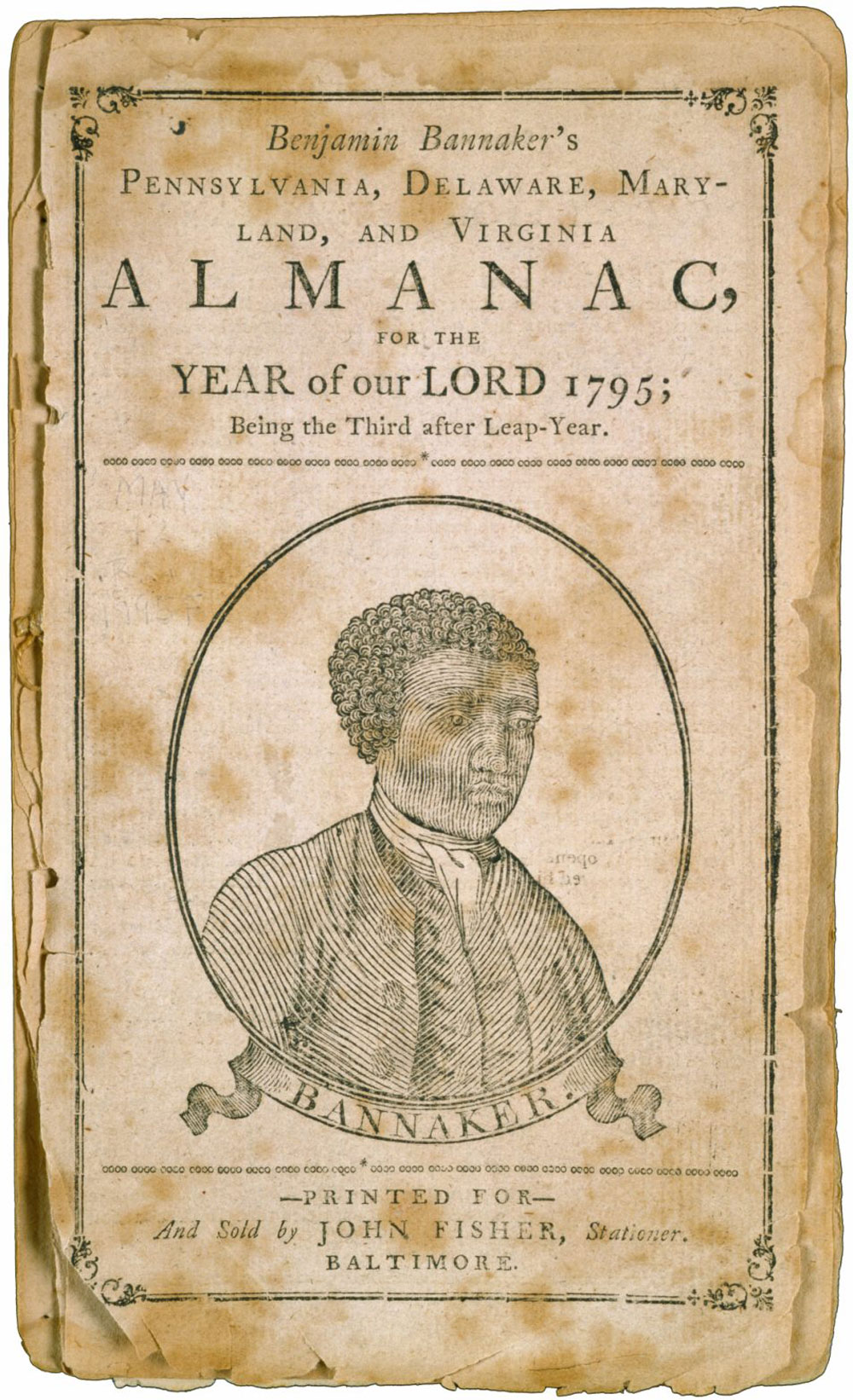

Mixing in words of wisdom and entertaining essays, Benjamin Banneker's Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanack and Ephemeris, for the Year of Our Lord 1792 was, according to the frontispiece, “a greater, more pleasing, and useful Variety than any Work of the Kind and Price in North-America.”

Supported by the Ellicotts and other leading Quaker abolitionists, and given further credibility by two prominent scientists — David Rittenhouse and William Waring — who vouched for the accuracy of his calculations, Banneker’s almanac was set to be an immediate success. But before its publication, Banneker felt compelled to send a copy to Jefferson alongside a 1,400-word letter.

In the letter, he pleaded that the slave-owning Secretary of State take action against “the almost general prejudice and prepossession which is so prevailent in the world against those of my complexion,” even quoting Jefferson’s famous egalitarian proclamation in the U.S. Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal.”

Jefferson’s reply suggested Banneker’s almanac had made an impact: “I considered it as a document to which your whole colour had a right for their justification against the doubts which have been entertained of them.” However, the exchange did not lead to any antislavery action, as Jefferson struggled with the ideas of race and liberty and continued to keep slaves until his death.

What the exchange did do, however, was provide Banneker with the means to influence public opinion in favor of abolition. Within a year, the correspondence had been circulated in a Philadelphia pamphlet, two magazines, and in the 1793 edition of Banneker’s almanac. He published the annual almanacs until 1797, his fame spreading throughout the U.S. and even to Great Britain, where William Wilberforce and other prominent abolitionists invoked Banneker’s name and works in the House of Commons.

F. Delventhal

Yet despite this newfound recognition in his winter years, Banneker remained a recluse. Having sold the remainder of his tobacco farm on the stipulation that he could spend the rest of his life on the land, Banneker retreated to his log cabin, where he continued his “unbounded desires to become acquainted with the Secrets of nature.”

Banneker passed away on October 19, 1806, aged 74. On the day of his funeral, Banneker’s cabin mysteriously burned down. Though the fire took many of his important journals and notes, it did not diminish his legacy as an inspirational scientist and important figure in the long journey to African American emancipation.

1

1

Comments

MVJEngland

July 25, 2020 at 5:56 am

A remarkable story, thank you for bringing it to my attention.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.