Use the stars of the Big Dipper to guide your way to beacons of spring’s night skies.

Akira Fujii

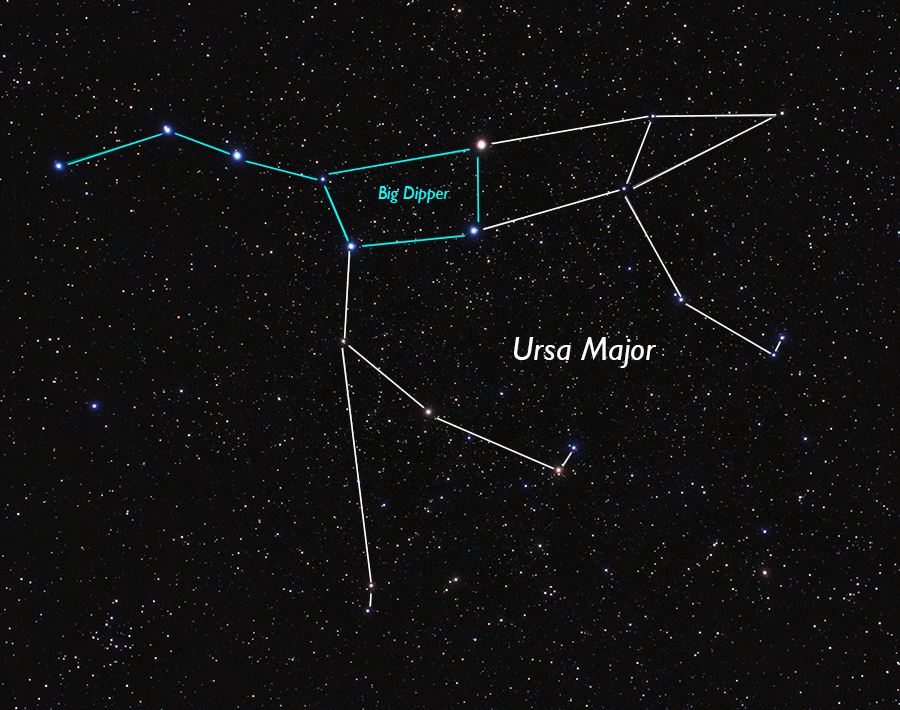

The Big Dipper is one of the most familiar sights in the Northern Hemisphere’s night skies. It’s a prominent asterism — a recognizable pattern of stars that isn’t an officially named constellation — in Ursa Major, the Great Bear. Ursa Major is a circumpolar constellation: Its stars never set for most observers at northern latitudes. In fact, the Dipper is visible year-round to observers north of latitude 41°, which makes it an invaluable key to unlocking the night sky.

Let’s look at seven sights that you can find with the naked eye on these spring evenings using the Dipper to guide you.

Akira Fujii

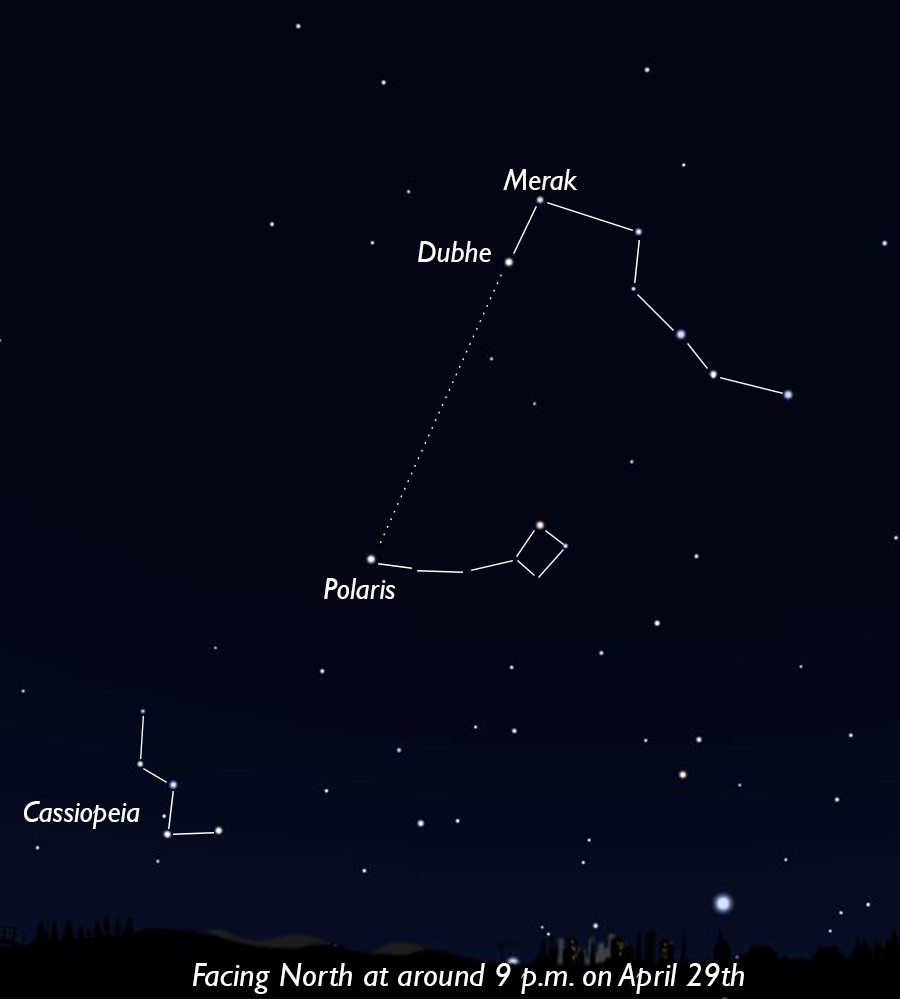

Polaris, the North Star

Throughout the course of the year, the Big Dipper appears to orbit Polaris, also known as the North Star, and the brightest star in the Ursa Minor, the Little Dipper.

Start by finding the two stars at the front end of the Dipper’s “bowl,” Merak at the closed side and Dubhe at the open side. These are often called the pointer stars. Now draw an imaginary line from Merak to Dubhe and extend it past the open top of the Dipper’s bowl. The first easy-to-spot star you encounter is Polaris, a triple-star system lying about 430 light-years away. It might surprise you how dim 2nd-magnitude Polaris looks — in fact, it’s the 50th-brightest star in the sky.

Stellarium

Once you find Polaris, maybe you can make out the rest of the Little Dipper. Its stars are often difficult to find under light-polluted city and suburban skies, but don’t get discouraged if you can’t see all of it. At least you’ve located the legendary North Star.

Cassiopeia, the Queen

Now continue the line through Polaris to the unmistakable W-shape of Cassiopeia, the mythological queen of ancient Ethiopia and wife of Cepheus. Cassiopeia is another circumpolar constellation (for Northern Hemisphere observers) and is always opposite Polaris from Ursa Major. To me, the two constellations don’t look like a bear and a queen, but instead remind me of a pair of dancers — the Dipper’s handle like an outstretched arm as they dance across the sky night after night.

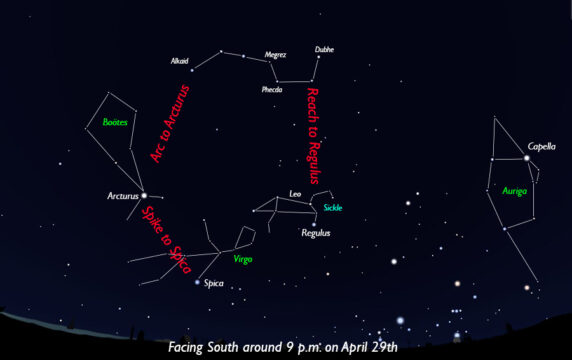

Regulus – the Little King

Let’s go back to the Dipper and follow the line between the pointer stars in the opposite direction, through the closed end of the bowl, to “Reach to Regulus.” Regulus is the brightest star in Leo, the Lion, so we could also “Leap to Leo.” It's a four-star system about 79 light-years away from us.

While you’re here, see if can make out the “sickle” asterism that marks the Lion’s front end. Regulus sits at the bottom of the sickle, almost like the dot at the bottom of a backward question mark. Regulus also marks one of the corners of the Spring Triangle, along with Arcturus and Spica, our next two stops.

Arcturus, Bear Guardian

To find the second star in the Spring Triangle, let’s follow the curve of the Big Dipper’s handle away from the Dipper’s bowl and “Arc to Arcturus.” This red giant, the brightest star in Boötes, lies about 37 light-years away. Arcturus is also the fourth-brightest star in the night sky and the second-brightest visible in most of the Northern Hemisphere. Billions of years from now, when the Sun has used up most of its fuel, it will swell into a red giant similar to Arcturus.

Spica – Ear of Grain

Now that we followed the “Arc to Arcturus,” we can continue on a straight line and “Spike to Spica,” the third corner of the Spring Triangle. Spica, Virgo’s lucida and a binary star, lies at a distance of around 250 light-years.

Stellarium

Capella, the She-Goat

Gorgeous yellow Capella is another quadruple-star system. It’s about 42 light-years away and is the brightest star in Auriga, the Charioteer. Capella always stops me in my tracks each fall when it’s the first of the Winter Hexagon’s stars to come back. One of my favorite things to do is to follow it each night until spring, when it’s the last of the Hexagon's stars to vanish into the dusk.

To find it, extend the line from Alkaid at the far end of the Dipper’s handle through Megrez (the star that connects the handle to the bowl) and Dubhe, across the top of the Dipper’s bowl. As the months go by, it’s fun to watch the Dipper turn as the little goat dances high overhead and across the night sky. Once you find Capella, can you locate the rest of the Winter Hexagon’s stars: Pollux, Procyon, Sirius, Rigel, and Aldebaran?

Deneb, the Tail of the Swan

As spring becomes summer, the Summer Triangle rises into the night. For those of you who like to stay up late during these mid-spring nights, you can find one of the Summer Triangle’s stars using the Big Dipper. Just as Dubhe and Merak are pointer stars for Polaris, let’s draw a line from Phecda at the handle-side of the bowl through Megrez, and let them point our way across the constellation Draco to Deneb in Cygnus, the Swan. Deneb’s distance from Earth is uncertain, but it likely lies between 1,500 and 3,000 light-years away and is one of the farthest stars visible with the naked eye. Once you’ve found it, see you should be able to find the other two stars of the Summer Triangle: Vega (in Lyra) and Altair (in Aquila).

The Big Dipper isn’t just one of the night sky’s most recognizable star patterns. If you know how, you can also use it as the starting point to find inspiring sights. Is there anything else you can find with it?

Akira Fujii

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.