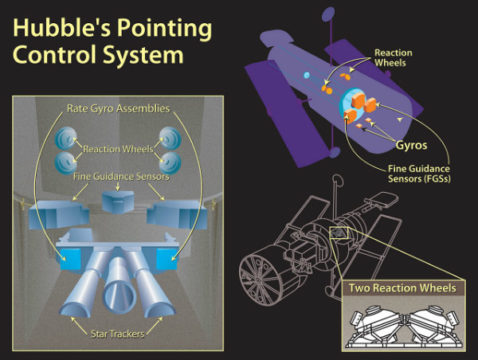

A failure of a gyroscope used to point and stabilize the Hubble telescope caused the observatory to safely shut down while engineers determine a fix.

NASA

Any machine that’s been running nearly continuously for 28 years is bound to break down every now and again. And the Hubble Space Telescope is no exception.

On October 5th, Hubble went into safe mode after the failure of a gyroscope that helps point and steady the telescope while it’s observing. During safe mode, the observatory hibernates while engineers on the ground figure out how to fix the problem.

“We’re proceeding carefully to make sure we don’t do any more harm,” says Tom Brown (Space Telescope Science Institute), head of the Hubble mission office. “Hubble will return to science whether or not we get the gyroscope working.”

During the final Hubble servicing mission in 2009, astronauts from the space shuttle Atlantis installed six new gyroscopes in the telescope. Typically, the observatory uses three at a time. When one fails, it then switches to one of its backups. Since the last tune-up, two of those gyroscopes have stopped working.

Last Friday, one of the three active gyros failed. The failure wasn’t a surprise; the gyroscope had been showing signs of wear and tear for the last year. However, the replacement gyro — the last in Hubble's arsenal — wasn’t performing up to snuff either. So shortly after 6 p.m. EDT, the telescope suspended operations to await further instructions from Earth.

STScI

What engineers know so far is that the backup gyro is pointing too far off its mark. “Ideally, the gyro points in the direction you need,” Brown explains. In reality, however, all gyros are off by a bit. Software can correct for that offset as long as it’s not too large. Right now, the discrepancy is outside the useable range.

NASA has convened a team of engineers to pore over data from the telescope as well as schematics and flight software to determine the next step forward. The best option is to get the replacement gyro working so that the telescope can go back to full operations.

If that doesn’t work, the agency already has a plan in place to operate the telescope with just one gyro while the second good one waits as a backup. In that mode, the observatory relies on additional intel from magnetometers and guiding cameras for accurate pointing. The downside, says Brown, is that then Hubble can look at only half of the sky at any given time. However, as Earth and Hubble go around the Sun, so does the telescope’s viewing window. Over the course of a year, the entire sky (minus the usual forbidden zone within 50 degrees of the Sun) becomes available.

"The mood for astronomers is confident and upbeat," says Hubble senior project scientist Jennifer Wiseman (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center). "We expect Hubble to be achieving excellent scientific observations of the universe for quite a few years to come, regardless of how this one malfunctioning gyro fares."

Brown concurs. “There’s not a feeling of doom, just a feeling of concern,” he says. All other instruments are in good shape. And while engineers tinker with the gyros, a team of astronomers from around the world is already on site reviewing proposals for coveted future time on the telescope. “We still expect to last well into the 2020s,” he says.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.