Earth’s new “minimoon” may in fact be a relic of the early Space Age.

NASA / JPL-Caltech

A suspected fragment of the early era of space exploration is paying Earth a visit for the next few months.

The 6-meter object was spotted by the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System 1 (Pan-STARRS1) automated sky survey on the night of September 17th, gliding near the border of the constellations Pisces and Cetus. Brought online in 2008, the PanSTARRS telescope on Maui, Hawai'i, scours the sky looking for comets and near-Earth asteroids. The Minor Planet Center in Cambridge, Mass., assumed the object was an asteroid, giving it a formal designation: 2020 SO.

IfA Hawaii / PanSTARRS / Richard Wainscoat / Eugene Magnier

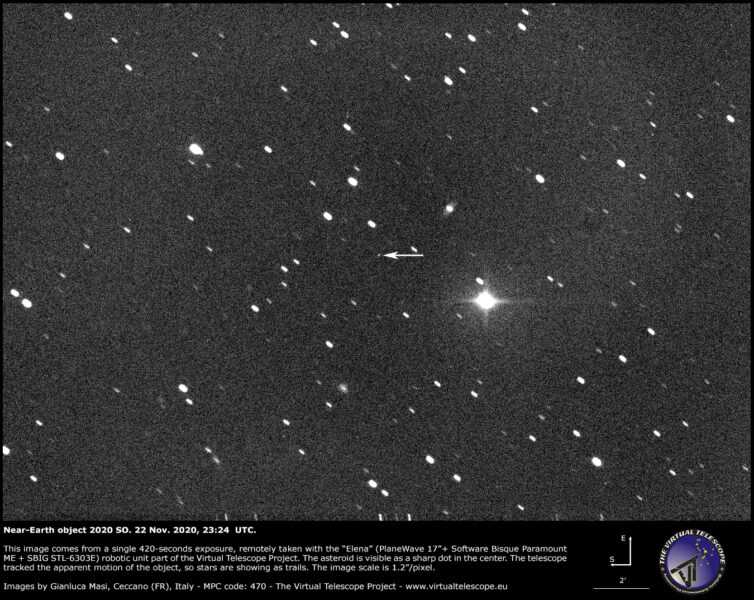

The object's apparent arc across the sky suggested it was closeby, and calculations later showed that Earth seems to have captured it as a temporary "minimoon." On November 8th, 2020 SO entered Earth's 3 million-kilometer-wide Hill sphere, the area within which our planet’s gravitational field dominates over the pull of other objects such as the Sun.

2020 SO will make two looping passes around our planet, coming closest to Earth on December 1st. (See a live video feed of the flyby from the Virtual Telescope!) On that day, it will pass within 43,000 kilometers (27,000 miles), just over a tenth the distance to the Moon and almost 8,000 km beyond geosynchronous orbit. It will return to a solar orbit early next year.

Asteroid . . . or Space Junk?

Near-Earth asteroid passes aren't unusual, but this discovery gave astronomers pause. Its orbit around the Sun was almost exactly in line with Earth's orbit, unusual for natural near-Earth objects.

Researchers used the Catalina Sky Survey in Arizona and the European Space Agency's Optical Ground Station in Tenerife, Spain, to carry out 170 additional observations of the object. Plotting its path over a three-month span (including pre-discovery/recovery observations going back to August), astronomers noticed that solar radiation pressure was pushing 2020 SO like an empty aluminum can on a windy day — indicative of a hollow object rather than a solid space rock.

NASA / JPL-Caltech

“Solar radiation pressure is a non-gravitational force that is caused by light photons emitted by the Sun hitting a natural or artificial object,” says Davide Farnocchia (NASA-JPL) in a recent press release. “The resulting acceleration on the object depends on the so-called area-to-mass ratio, which is greater for small and light, low-density objects.”

Note to readers: I followed up with Dr. Farnocchia at JPL to clarify his statement, and while the solar wind (charged particles from the Sun) does indeed exert pressure on spacecraft ,the pressure seen in the case of 2020 SO is from "acceleration due to the momentum that photons carry (solar radiation pressure)." -Dave Dickinson

Space Age Herald

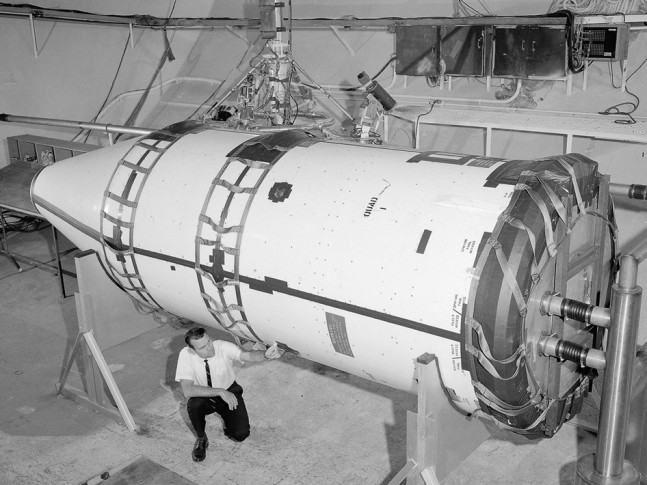

One sort of hollow object occasionally found in the Space Age is a discarded rocket booster. Lunar exploration from the early 1960s through the 1970s generated several such objects. Many smashed on the Moon, such as the Apollo 16 booster impact site, spotted by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in 2016. Others were simply injected into orbit around the Sun.

Some notable examples include the Apollo 10 Snoopy module, the enigmatic object 2010 QW1 (which turned out to be Long March 3C upper stage from China's Chang'e-2 mission), and J002 E3, which turned out to be a Saturn upper stage from Apollo 12. In the latter case, its identity was cinched by spectroscopic analysis, which noted a titanium dioxide coating matching the white booster paint of the Apollo era.

But which mission did 2020 SO originate from? Armed with a large set of observations, Paul Chodas (CNEOS, JPL) ran back the clock on asteroid 2020 SO — and found it was last near the Earth-Moon system in late 1966.

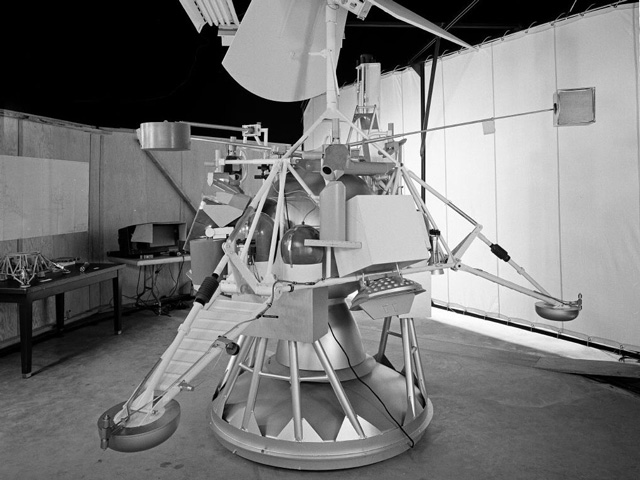

The timing coincides with Surveyor 2, an ill-fated mission to the Moon that launched from Cape Canaveral during that time.

“One of the possible paths for 2020 SO brought the object very close to Earth and the Moon in late September 1966,” Chodas says in a recent press release. “It was like a eureka moment when a quick check of the launch dates for lunar missions showed a match with the Surveyor 2 mission.”

NASA / Glenn Research Center,

The Surveyor series of automated landers were precursors to the crewed Apollo landings. Surveyor 2 was set to land in the Sinus Medii region of the Moon, but a faulty thruster doomed the mission. Instead, it struck the nearside of the Moon near Copernicus Crater on September 23, 1966. The Centaur upper stage, however, missed the Moon and headed out into solar orbit.

NASA

Why is this discovery and recovery of an old rocket booster important? Well, in addition to the accumulation of debris in low-Earth orbit, we’re sending out space junk into solar orbit as well. A recent study looking at objects in high-Earth orbit suggests that we may not be adequately tracking most of what’s currently up there. As time goes on, these relics will become testaments to the era of the early Space Age, worthy of a museum. There’s even a certain Tesla Roadster out there as well, sent into heliocentric orbit during the inaugural launch of SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket in early 2018.

Gianluca Masi/The Virtual Telescope Project

You can see the museum-quality piece of history for yourself. In the early morning hours of December 1st, SO 2020 will make its closest pass from us at 3:57 a.m. EST (8:57 UT), shining as an 11th- or 12th-magnitude "star." Moving at about 10 degrees per hour through the constellation Virgo, it will best be visible from the Americas in the dawn sky. This close pass will give astronomers a chance to examine 2020 SO’s spectra and albedo, to get a better grasp on its current state and rotation. After 2020 SO departs in early 2021, we won’t see it again until 2074 on a distant 0.01 AU (~930,000 mile) pass.

5

5

Comments

Stephen Gagnon

November 21, 2020 at 5:06 pm

There's a disconnect here. The solar wind is not the same thing as radiation pressure.

"...astronomers noticed that the solar wind was pushing 2020 SO like an empty aluminum can on a windy day..."

"Solar radiation pressures is a non-gravitational force that is caused by light photons emitted by the Sun hitting a natural or artificial object..."

You must be logged in to post a comment.

David DickinsonPost Author

November 22, 2020 at 9:26 am

Thanks, Steve... correct'd.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Larry McNish

November 23, 2020 at 11:20 pm

Man is that thing moving!

Celestial path sky chart for those that can't find one.

Path for Nov 30 to Dec 2 (UT) is shown in magenta.

https://grumpyoldastronomer.com/2020SO/2020SO_Celestial_Path.png

You must be logged in to post a comment.

David DickinsonPost Author

November 24, 2020 at 8:29 am

Thanks for making a map for the celestial path of 2020 SO, Larry. Keep in mind, the passage is close enough that parallax will play factor. I'd use JPL/Horizons to generate an ephemeris for precise RA/Dec positions over time.

Thanks,

Dave

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Larry McNish

November 25, 2020 at 4:02 am

Yup - Because the orbit is so dynamic, that's exactly what I did for my viewing location. I grabbed the HORIZONS data and plotted it with my own star-charting program.

Also - Nov 30 is a full Moon night so imaging a 14th mag object a few RA hours away from the Moon that night or the next is probably not going to happen.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.