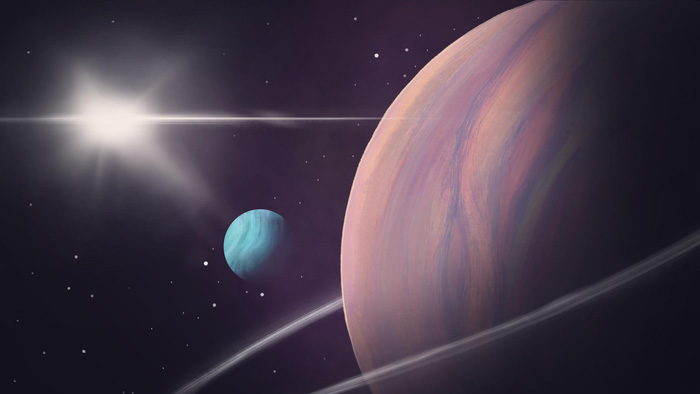

Astronomers may have found a second Neptune-size exomoon hidden in the retired Kepler space telescope’s data.

Helena Valenzuela Widerström

Despite an explosion of exoplanet discoveries since the 1990s, astronomers have not confirmed the discovery of a single exomoon. In fact, only around a dozen exomoon candidates have been put forward up to now.

In 2018, David Kipping (Columbia University) and Alex Teachey (now at Academia Sinica, Taiwan) were the first, tentatively reporting a possible Neptune-radius moon about 7,800 light-years from Earth: Kepler-1625 b-i. Now, the astronomers and other colleagues have announced the discovery of another exomoon, published January 13th in Nature Astronomy. However, just as before, they urge both caution and the need for further observations.

The putative exomoon, designated Kepler-1708 b-i, was found 5,600 light-years away, orbiting a Jupiter-size planet around a star similar to the Sun. The planet is on a Mars-like orbit, at about 1.6 astronomical units (a.u.). Its moon orbits about 12 planetary radii away, similar to Europa’s distance from Jupiter. Unlike Europa, though, Kepler-1708 b-i is huge, about 2.6 times Earth’s radius. This means the moon would be unlike any satellite in our solar system.

“I'm not sure what the actual composition would be,” says Kipping. “It could be just gas all the way down, a ball of ocean, or a rocky planet with a thin hydrogen envelope — we just don't know.”

The starting point for Kipping and colleagues’ discovery came with their Kepler survey of 284 relatively close-in planets. It turned up only one candidate exomoon (Kepler-1625 b-i), which made Kipping wonder whether large moons are more commonly found around planets that lie further from their host stars.

To test this idea, the astronomers conducted a survey of cool gas giants in the Kepler archive. After removing unsuitable and poor-quality data, they were left with 70 planets detected at least twice by Kepler. They then looked at the dips in starlight created by the planets as they passed across the face of their stars in more detail, keeping only those dips that fit better with a planet-moon scenario.

Only three planets passed this test, but detailed vetting whittled down the candidates even further. “In one case, we're pretty sure it's two starspots causing modulations in the shape of the light, which look like a moon,” explains Kipping. “Another case we've been able to reject because we think it's actually something to do with the instrument.”

This left Kepler-1708 b-i.

As a final check, the team created a fake signal that would match the host planet alone and injected it randomly into the Kepler data of the host star to see how often they would erroneously claim there to be an exomoon present. When they did this 200 times, there were just two occasions where the data falsely suggested there was an exomoon.

“There's a 1% chance that this is just the data fluctuating in a really evil way that conspires to trick us,” Kipping explains. “It's both a small number and uncomfortably large.” To confirm Kepler-1708 b-i’s (and indeed Kepler-1625 b-i) status as an exomoon, Kipping concedes more observations are required.

“This is an excellent analysis, but even so this is still just a candidate,” says Mary Anne Limbach (Texas A&M University), who was not involved in the study.

Laura Kreidberg (Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Germany), who conducted follow-up studies that called the previous Kepler-1625 b-i discovery into question, also says that Kepler-1708 b-i is one of the most promising candidates yet identified but needs more data: “We would need to see another transit observation that shows two dips in brightness: one caused by the planet blocking light from the star, and one from the moon blocking the light.”

However, such observations won’t be made any time soon. Kepler was retired in 2018 and the most capable instrument currently available to make this measurement — the recently launched James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) — is heavily oversubscribed. Also, Kepler 1625 b’s 737-day year means it won’t pass in front of its star in 2022.

Looking further into the future, the outlook is brighter. Kipping is sifting through Kepler data using a more advanced technique to spot additional exomoons. He’s also planning a Hubble Space Telescope or JWST survey for small exomoons the size of Europa or Ganymede.

“Over the next decade, several telescopes will be coming online that are sufficiently sensitive to detect exomoons,” Limbach says. That list includes the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope as well as a new class of ground-based observatories — the Extremely Large Telescope, Giant Magellan Telescope, and Thirty Meter Telescope. “I think this is likely to accelerate the field on several fronts and could lead to the confirmation of the first exomoon within the next decade.”

1

1

Comments

Rod

January 14, 2022 at 1:00 pm

Okay, the .eu site is updated now with 1708 b and 1708 b-i with properties shown. http://exoplanet.eu/catalog/kepler-1708_b/, and http://exoplanet.eu/catalog/kepler-1708_b-i/ The NASA site is updated too, https://exoplanetarchive.ipac.caltech.edu/overview/Kepler-1708 b#planet_Kepler-1708-b_collapsible

I use both sites in my MS ACCESS DB. These two sites update frequently.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.